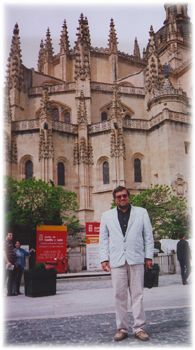

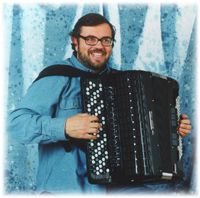

In the world of contemporary music the name of Vladimir Danilovich Zubitsky, Honored Artist of the Ukraine, winner of the 'World Cup - 75', composer-laureate of numerous international competitions, needs no introduction. He is a man with an extraordinary gift for music, equally brilliant as performer and composer. Many of his compositions are to be found in the repertoires of the most famous Ukrainian and foreign bayanists, accordionists, violinists, choral and symphonic conductors. In recent years the composer has lived and worked in the West. During a brief visit to Kiev, which he made in order to take part in the festival 'First Performances of the Season', he was interviewed by the well-known Ukrainian musician Anatoly Andreevich Semeshko, teacher, Honoured Artist of the Ukraine, professor, secretary of the National Ukrainian Musicians' Union, vice-president of the Ukrainian Association of Bayanists and Accordionists.

Q: Vladimir Danilovich, first of all, let me welcome you most sincerely to the Ukraine. Knowing your heavy schedule and your intensive regime, I would like to ask you, nevertheless, as an old and trusted friend, to accede to my request, to the request of the editor of Narodnik, to appear in the pages of this popular Russian publication with your reminiscences, your thoughts on the present and the future? A: Thank you very much for this invitation to appear in Narodnik. Of course, Anatoly, I can refuse neither you, as a friend, nor the editor. I know this publication quite well - I think very highly of it. I am trying, belatedly, to meet all its 'requests'. Q: That's splendid. You won't object if I concentrate the topics of our conversation under four main headings - biography, performance, composition and music in society? A: Not at all. Q: Well, as they say, here goes. It is clear that the dry 'black-and-white' of reference books, encyclopaedias, or other similar publications, does not give the reader a true impression of the man, not to mention the artist. So tell me, if you will, about your 'musical universities', your teachers, how you became a performer and a composer? A: I think I would be right in saying that my 'musical universities' were my early childhood, my own family. My parents were extremely gifted musicians. My father, Danilo Nikiforovich, who played practically all the South-Ukrainian folk instruments, dreamed, as a young man, of becoming a musician. A genuine love of instrumental folk music, the wish to study and an irresistible passion led him, even in the post-war years, to enrol in the Odessa Conservatoire to study the balalaika. It is quite possible that he would have enjoyed a brilliant career as a folk musician, but unfortunately the difficult financial circumstances of his parents and himself, forced him to abandon his cherished dream. Having completed his training as a medical assistant, my father returned to his parents in the village of Goloskovo. And it was there, after meeting my future mother, Anna Artemovna, a beautiful, gentle, good human being, a woman with a great loving heart, that our family was born. Gradually it grew; after the birth of my elder brother, Alexander, in 1953, I appeared on the scene to complete the family quartet (laughter). Joking apart, in the following years we very often performed as a family quartet. My brother soon became adept on wind and percussion, as well as folk instruments, my mum sang beautifully, my father, as I've already said, could play practically any instrument that came to hand. I, as the youngest, was first given the accordion, and then the bayan. Of course, the family musical evenings were of an amateur nature, but they were always very successful. They say that the oldest inhabitants of Znamenka remember our 'peformances' to this day. They were wonderful times. I was surrounded then, by people who were poor, simple, wonderfully good and spiritually rich. I remember so well the indescribable beauty of the Ukrainian countryside; the woods, the lakes, the excitement of our childish fishing trips. I specially remember the noisy Znamenka market, (our home was next to it), the harmonious instrumental groups, the Ukrainian songs, the jokes, the language, the dances and, at times, the punch-ups. Q: Was it not just these childish impressions which formed the basis of your choral concerto, The Market? A: Oh, without a doubt, although my Market was somehow more cultured, more 'academic'. Q: Well, let's move on from your roots, if I can put it like that, to your teachers? A: It's hard to disentangle the two themes, since my father was, once again, my teacher. It was precisely he, who seeing my musical aptitude, decided that his youngest son could - and should - fulfil his own dream of becoming a professional musician. And so he sent me to the Znamenka Regional School of Music. My first official teacher was Alexander Afanasevich Usatiuk. Q: To whom you dedicated your Ukrainian Suite? A: Absolutely true. I dedicated this work to my first teacher as a token of my profound gratitude. I am eternally indebted to this extrovert, sociable man, a multi-talented musician, who played like a master, with or without music, who not only wrote poems, but set them to music as songs. It was then, in Znamenka, in the person of my teacher, that I first saw a living composer (laughter). Q: Did you think then, in Znamenka, that music could become your future profession? A: Well of course not. At first I really enjoyed my studies at the Children's School of Music but I still dreamed of the sea. And since we lived in the semi-steppe zone of the Ukraine, the very beautiful and picturesque lakes were seas to us small boys. It was my passion. Seizing my rod, I would rush to the lake as though I were meeting my childish dream. But these dreams of the sea were doomed to be dashed on the breakwater of fatherly severity. I began to neglect my studies. Unfavourable remarks began to appear in my school reports. There was nothing left for my father to do but to apply the methods of an old fashioned country pedagogue. In short, in the presence of witnesses, roles played once again by my father and elder brother, I was obliged, in floods of tears, to burn all my fishing tackle and promise, faithfully, to 'come to my senses'. Soon after the collapse of my dreams of the sea, the family moved to the large industrial centre of Pridnepr, to that giant of the mining and metallurgical industry in the Ukraine, the town of Krivoi Rog. Q: I remember your coming to Krivoi Rog very well. At that time, it was in 1967. I was in my third year at the College of Music, which was in the same building as the School of Music No.1, to which you'd been moved, if I remember rightly, in class 5. And immediately after your first school concert, the bayanist elite, including your new mentor Nikolai Andreevich Potapov (head of the college's folk-instrument department), started to talk about the appearance of an extraordinay child prodigy called Vladimir Zubitsky. A: Well that's an obvious exaggeration, although I had to undergo the familiar methods applied to prodigies (laughter). My Krivoi Rog mentor, seeing that, periodically, I would grind to a lazy standstill, used to lock me in the classroom for three or four hours, leaving me there alone with the works of Czerny, Kramer and other famous writers of educational/technical material. Today I understand perfectly well why he adopted these radical methods of teaching a gifted young person (laughter). Well, speaking seriously, Potapov was indeed the first serious teacher of music I encountered. He was a very demanding instructor, one of the best graduates of Kiev Conservatoire, where he and Vladimir Besfamilnov studied under Nikolai Ivanovich Rizol'. It was thanks to the persistence of Potapov, with his progressive professional views that my father had to 'shell out', again and again, and buy one new bayan after another, already free-bass! Beginning with that 'revolutionary' instrument, the 'Rubin'. That opened up an entirely new repertoire and extended the expressive possibilities. It was precisely there, in Krivoi Rog, after completing the course at the Children's School of Music, that I began to think seriously about my musical future. With the support and blessing of my parents, I joined the Krivoi Rog College of Music and continued my studies under Potapov. At the end of 1968, when you had already left the College for the Kiev Conservatoire, Anatolii Alekseevich Surkov came to Krivoi Rog to conduct a seminar on teaching methods at the Children's School of Music. Having heard me, among other young bayanists, he strongly advised Potapov (who was by then suffering from a terminal illness) and my parents, that I should continue my musical education in Moscow. Thus, after finishing the first year at the Krivoi Rog College, I became a second-year student at Moscow's Gnesin Institute of Music, under a brilliant, striking musician and no less striking personality, Vladimir Nikolaevich Motov. My two years of study with Vladimir Nikolaevich were extremely useful. I received not only an excellent professional training, but a lesson in true humanity. Q: What was the foundation of Motov's approach to teaching? What were his predominant directions, so to speak? A: I could say so much about it, but I know I need to be concise. So I'll try to answer briefly: first - educating the ability to improvise, second - stimulation of intellectual growth, third - ensemble playing, fourth - the development of orchestral thinking (Vladimir Nikolaevich Motov constantly underlined his view that the bayan is a great orchestra). Q: Were your first experiments in the field of composition connected with the Moscow period? A: Not entirely. I made my first tentative attempts while I was still at Krivoi Rog. They were miniatures which arose more or less as free improvisations. The first conscious attempts were really connected with the years of study under Motov, who supported this sphere of my activity with his interest and approval. Essentially, he was my first composition teacher, for which I am eternally grateful. Q: Did the actual atmosphere of such a celebrated cultural centre, as Moscow then was, provide its own stimulus? A: Undoubtedly. At first I was literally stunned by the world, or, rather, by the diversity of the world of great art in the capital. In those days the doors of all the concert and exhibition halls were open to us. A student ticket served as a pass. Q: Which of the Moscow musical 'events' made the most lasting impression? A: The concert given by Vladislav Zolatariev at the Gnesin Institute made an indelible impression. For the first time I heard his symphonic concerto, played by Viacheslav Galkin, conducted by Veronica Dudorova. I tell you honestly - at that moment everything changed for me. I discovered a new instrument for myself, the completely new, extraordinary world of imagery of Zolatariev's music. I was shaken by the philosophical monumentalism of the composer. I understood that, thanks to his music, I was a happy witness to the conception of the bayan as an academic instrument. Q: Which bayanists did you manage to hear at that time? A: Very many. At that time, the main platform for bayanists was in Moscow, at which Motov's pupils regularly made their debuts, particularly on the occasion of the bayan evenings which were held there. After such concerts Motov would conduct a detailed group analysis of everything seen and heard. You know, for us youngsters it was a fantastic school. In Moscow I encountered, for the first time, the art of such performers as Friedrich Lips, Iurii Vostrelov, Valerii Petrov, Aleksandr Skliarov; I first heard Vladimir Besfamilnov. It was a meeting which determined my future. Q: As I understand it, the smooth transition to your Kiev period matured there? A: Yes, I think so. Q: So, after completing your third year at the Gnesin Institute, you returned to the Ukraine to study at the Kiev Conservatoire? A: Not exactly. When my performance there was awarded a 'good', I went to Motov for advice. He reacted very favourably and gave his blessing to my plan. Today it seems to me that his behaviour to me then underlines, yet again, the extraordinary quality of the man. At that time I really wasn't the least of the bayanists at the Institute. Another year of study under him there would have paid handsome 'dividends' to Motov, as a teacher. But he was above personal ambition and self-interest Q: What works did you choose for your audition? A: I won my place at the Conservatoire with the G minor Fantasia and Fugue of Bach, Beethoven's Twelve Variations on a Russian Theme, something else (I don't remember now), and my own First Children's Suite. Q: Yes, it's not every student who could present such a program for his entrance exam. But I have something else in mind. From the moment you came to the Kiev Conservatoire, where I was then studying, our paths crossed again. And once again, I remember, what a 'stir' you created in Kiev's bayanist circles. Once again they began to talk about a performer who was no longer an 'infant prodigy', but a 'youthful prodigy', stunning everyone with his mastery of his free bass multi-timbre instrument, with his writing, his knowledge of the repertoire, his fantastic improvisations and so on and so on? A: I think you're exaggerating again. I played, I wrote, I listened, I improvised any way I could, that's all - I could do it neither better nor worse. Q: Well, all right, I won't argue, I'll just say that it is my profound conviction that your arrival in Kiev gave a very important stimulus to the growth and improvement in professional orientation of the bayanist students. You were a beacon for them, by whose light they guided their performance, although, as it seemed to me then, it was a light which attracted open hostility from some of the 'bosses'? A: I know. I felt it, too, in the attitude of certain teachers to me and to Besfamilnov, and in their outspoken comments on virtuoso selections and academic concerts and so on. Ah well, let's not stir up the past, God is their judge. Q: Very well, but I'd like to pursue the subject of the positive and progressive teachers, those who continued to lead you into the orbit of great music. When you enrolled at the Conservatoire you made a written request to study with Besfamilnov, who at that time was just beginning his teaching career. Why particularly with him? A: Well, in the first place, as I said, after that musician's Moscow concert, he became for me the bayanist's ideal; in the second place, I very much wanted to be taught by a performer; and, in the third place, I sensed intuitively that at that stage this was the man and the musician I needed. Q: As far as I remember, your intuition didn't let you down? A: Absolutely true. I am infinitely grateful to Vladimir Vladimirovich (Besfamilnov), to this amazingly intelligent and subtle man, this wonderful musician, who dedicated himself entirely to us, his first pupils. There were only a few of us, but we were all good friends and hard workers. I remember those years with Vladimir Vladimirovich with enormous warmth. Q: Was the actual atmosphere of bayanist Kiev different from the Moscow 'micro-climate'? A: At that period there was undoubtedly a difference. Above all, in the instruments. The free bass bayan had not really taken off in Kiev. And this in spite of the fact that the free-bass enthusiast Stepan Grigor'evich Chapkii lived and worked there, demonstrating at every level and from every platform the advantages in an instrument of this new construction. But its voice didn't appeal to everyone. That, so to speak, was the negative side of things. I would say that one of the most positive aspects of the Kiev school was its policy on the teaching repertoire (though that wasn't without its problems). The Kiev bayan school relied on the classics. You must remember, we played practically nothing but classical music. Many of them played the romantic composers. The policy bore lasting artistic fruit. The Moscow bayanists at that time, while not neglecting the classics, were more adventurous in introducing original music (that of Vladimir Zolatariev), which significantly enriched their repertoire. Later the Kievans would take the same route. Q: Good. Well, let's go back to your years as a student, your teachers. How did you, a performer with a brilliant future, find yourself in the faculty of composition? A: It was all very simple. As I had done in Moscow (I showed all my compositions there to Motov), I showed my works to Vladimir Vladimirovich. When he heard them he immediately introduced me to Miroslav Mikhailovich Skorik, who at that time was teaching composition at the Conservatoire. I considered and still consider him to be one of the most outstanding musical figures of the second half of the twentieth century. My years of study with him coincided with the most fruitful period in his creative life. If I may say so, they were years of mutual creative enthusiasm. But my creativity as a composer really 'took off' in my second year at the Conservatoire, that is, in 1972, when I became a student in two faculties - orchestral and composition. Q: Whenever does the third, operatic-symphonic faculty appear in your biography? A: Having graduated from the orchestral faculty in 1976 while remaining at the Conservatoire as a student-composer, I enrolled in the operatic-symphonic faculty in that same year, under Professor Vadim Borisovich Gnedash, National Artist of the Ukraine, head of the Ukrainian radio and television orchestra for more than seventeen years. In 1977 I received my diploma as a composer, and in 1979, after conducting my own first symphony and Rachmaninov's Aleko for the state examination, I qualified as an operatic and symphonic conductor. Q: Yes, your student days were far from typical. But all the same, what made you take up the conductors' baton? A: You know, it's not a matter of the conductors' baton. It's a very interesting and far from simple question. I could speak endlessly on the subject. But I'll answer you as briefly as possible. I am convinced that any musician, whatever his speciality, should follow the conductors' course. They won't all end up on the professional conductor's rostrum - God forbid. To me, as a musician and a composer, conducting gave so much. I got to know the orchestra 'from the inside', as it were, I learned to see and hear it internally. Now, working on a score, I know exactly how it should be notated, what is the most digestible form, from the point of view of an immediate, convincing, resonant performance. Gnedash gave me a lot of very wise advice on the subject. I remember it with warmth and great gratitude. Q: All the teachers you have named (apart from Krivo Rog's Potapov), are still flourishing today, as far as I know. They are modest people, but I am sure that they are secretly proud to have taught such a pupil as Vladimir Zubitsky. I think that every one of them would have gone down in musical history if they had taught only you. Do you manage, with all your current commitments, to keep in touch with your mentors? A: Yes, of course. I maintain the warmest, closest possible relations with all my teachers. Q: Still on the subject of music teaching, I want to ask you another question. We all know so well that, in the early years of any serious musician, especially before he is established, there are, if I can put it like that, unofficial teachers, in whose classes he never enrolls. What is more, these teachers often live and work in other towns, even in other countries, but, in spite of that, their creativity, their mastery exerts such a strong influence over young people that frequently, though they themselves may be unaware of it, they sometimes become mentors for whole generations. Did you have any such teachers? A: Oh, undoubtedly. If we're talking about composition, then my unofficial teachers were such greats as Bartok, Stravinsky, Honegger, Berg. Of all the contemporary composers who have exerted the most positive influence, or so it seems to me, I can name Skorik, Terterian, Stankovich, Shnitke, Cancelli, Shedrin and, of course, Vladislav Zolotariev. Q: But what about specialists in the bayan? A: I always had - and have - the greatest appreciation and respect, as far as performers are concerned, to the repertoire policy of Friedrich Lips. Today you can learn a lot from the young people, but that's already another generation. Q: In conclusion, I can't resist asking the question: In their autobiographies, in notes on CDs, numerous Western-European performers (particularly Claudio Jacomucci, Chiachiaretta, and others), name you as one of their teachers. How do you feel today about the teaching of music? A: I started teaching very late and, if I am honest, somewhat reluctantly. It happened when I was already in the West, where it is hard to make a living solely as a performer. There, as a rule, all the well known performers and composers engage in teaching, to a greater or lesser extent; some work in conservatoires, some in academies, a third group take private pupils, a fourth prefer to give master-classes. I include myself in this last group. Working in seminars (master-classes) I usually appear as both performer and composer, that is, I am frequently asked to work on one of my own compositions. Among the performers who approached me with such a request were those young Italian musicians whom you named in your question. Q: The same, in spite of the 'fragmented' nature of your periodic bouts of teaching, if I can put it like that, I am curious to know, what is your pedagogic credo? A: The main thing for me is the development of the student's imagination. The fantasy, the idea, should always exceed the final result. However well a musician plays, his fantasy is always more perfect. For that reason it is important to inculcate in the student elements of the composer's talent: when the wished for result arises first as a fantasy, and only then is the method, the technique developed which can support this fantasy. If you start with the method, it is very easy to reduce a fantasy to the movement of bellows and fingers. It is something which happens very, very frequently in bayan teaching circles. It is precisely this approach which produces solid, reliable music teachers, who can talk and quarrel endlessly about every possible 'head-in-the-clouds' theory, about the secrets of micro-intoning, about the height to which each separate finger should be lifted, but who are never moved to tears by Music - it seems to me the most terrible thing that can happen to art in general, and to music-teaching in particular. Q: It would be hard for me to disagree. I share your views completely. In other words, you evidently have in mind a reasonable balance between the flight of the creative imagination and technique, by which 'the imagery of tonality' should always dominate, that is the artistic aim should engender technical prowess, but never the other way round? A: Yes, if you like, you could put it like that. Q: Before we come to the end of the biographical part of our conversation, I can't avoid the question which intrigues many of our colleagues. What was the reason for your departure to the West, to Italy? You must admit that to make such a radical change in your life, to the life of your family, you must have had some very serious reasons. What lay behind this decision - our Ukrainian 'obstinate independence', creative dissatisfaction, or some other reason? A: It seems to me, you've over-dramatized the question. This is the beginning of the twenty-first century, we live in a fairly democratic world, so one must regard such phenomena far more simply. My going to Italy was not in any way connected with some sort of political sub-text or a change of citizenship. To a large extent it is to do with creativity, with the necessity of more active creative contacts with Western Europe. In this respect Italy is very conveniently situated. My connections with Eastern Europe remain just as active and close as ever. I give concerts practically every year in the Ukraine and in Russia, in Kazakhstan and in the Baltic countries. Q: That is, as I understand it, you're on a sort of lengthy creative mission, while remaining a citizen of the Ukraine? A: Precisely. I am, and will remain, a citizen of the Ukraine, wherever I may live, and I don't mind telling you I'm proud of it. Q: Now, if you've no objection, I'd like to touch on the question of your work as a performer. It is well known that, not so long ago, in order to compete in the International Olympiad, you were obliged to go through the far from simple All Union Selection 'X-ray'. That fascinating, one could say heated competitive movement had its negative as well as its positive aspects: stars were discovered, careers were ruined, there was the official and the less than official awarding of places to competitors in the final, international stage of this exhausting competitive marathon, there were the record-breakers, who had 'worked their way through' 8-10 selections, etc. However many such hearings did it take you to convince the demanding jury, 'conforming', as they were, to international demands? Which of them did you yourself consider the most successful? A: Interesting question. Of course, as you say, this feverish movement had its positive moments; bayanists from the whole of what was then an enormous country were tuned to the pitch of those All-Union selections in one great upsurge. It provided a stimulus to work, to repertoire research, to the perfecting of performing and teaching skills. Candidates recommended for participation in international competitions were practically regarded in the same light as the Soviet space heroes. But to get into that 'group of cosmonauts' was, of course, extrordinarily complicated. I'm not going to talk about the negative aspects of the All-Union selections; I'll just say that there were more than enough of them. At the same time, it was then the only path to the international arena for young performers. Today we all understand that only too well. As far as my 'pre-cup' biography is concerned, if my memory serves me right, I worked my way through four selection performances. I began in 1972 in Leningrad (as a first-year student), and completed my 'laureate campaign' at the Ufim competition of 1975. I think the first, the Leningrad competition was my most successful. Q: It is well known that your brilliant career as a performer began immediately after your triumph at the Helsinki competition. In no time at all, you were giving solo concerts throughout the Soviet Union; you were known as a performer to numerous concert goers in the near east and the USA? A: There are a lot of layers to that question. I'll try to answer them one by one. In the first place, even stretching it to the limits, you can hardly call the beginning of my career as a performer brilliant. Immediately after the 'World Cup -75' I returned to Moscow with the then fashionable label, 'permission to travel refused'. Q: What? I thought I knew your biography inside out? A: At that time, not even my family or friends knew about it. However, the 'right' people knew about it, as did several of the Soviet delegation who returned home after the competition. Q: All the same, that's what happened in those distant days of 1975? A: I wouldn't want to focus too much attention on it - these memories don't give me any special pleasure. I'll only say, that the main reason was the Russian-language edition of the Bible, given to the members of our delegation on Helsinki station by an unknown woman who introduced herself as a well-wisher. Q: Is that all? A: In those days that was quite enough. The sacred text, or rather its presence in our possession, was given a particular interpretation in those days. As a result, travel, even to friendly socialist countries, was forbidden me for seven long years. Q: Yes, that really was a stalled take-off? A: Well, my wings weren't broken, thank God. In any case, the 'flight' continued, though at a strictly controlled and extremely limited height. Every year, under the auspices of 'Soiuzkontsert', I gave 40 to 50 concerts. I must admit that it gave me the most intense joy. The joy of communicating with colleagues, with vast audiences in the farthest corners of the Soviet Union. And I must admit, too, that all my energies in that period were concentrated on composition. I consider that those years were extremely fruitful ones for my creativity. I composed 7 symphonies, 3 operas, 2 ballets, 3 concerti for orchestra, three choral concerti and a lot of chamber music. In 1977 I was made a member of the Union of Composers of the USSR. Q: Did you never long, during those years, to dedicate yourself absolutely and completely to composition? I remember very well that you were the most outstanding figure in the group of young Ukrainian symphonic composers. I remember how you literally burst into that milieu with your orchestral piece, 'Concerto-Rustiko', while you were still a student at the Conservatoire? A: To be honest, to be perfectly straight with you, the longing did arise, and repeatedly, but some sort of mysterious force would not allow me to betray the instrument which had led me into the orbit of great music. I didn't abandon the bayan. Q: Thank God that you didn't, otherwise we wouldn't have been able to talk about your evolution as a performer? A: At the beginning, when I was just starting out on my performing career, I remember that I played a wide variety of music. I adored colourful, effective, technically brilliant music - I loved playing it myself, I was thrilled to hear others playing it. As a youthful performer I lived with Bach, Scarlatti, Mozart, Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Liszt, Rachmaninov, a little later Stravinsky, Barber. Of the music written for the instrument I played Chaikin, Miaskov, Lapinsky. But most of all I played my own works. What I practically never played on the platform were arrangements of folk songs and dances. A lot of people reproached me for it, but it was and remains the policy to which I adhere. Q: Are there works which remain unheard, unfinished? A: Yes, without a doubt, there are. But the thing I regret most of all now is that I didn't write, during those years, several concerti for bayan and orchestra. I would have been able, at that time, to play with orchestras in Kiev, and on tour. Today, especially in the West, to play with an orchestra or make a CD is a near unattainable dream. For that you need serious money. Q: Those works which you studied in your youth, i.e. at the beginning of your artistic life, what happens to them? Have you had to clear out those temporary 'accumulations' from your repertoire, in order to see it in a new light? A: Of course I've had to, and more than once. It's just that - the clearing out of temporary 'accumulations' as you call them. It's a matter of re-interpretation, without which no work can survive in the repertoire. In time, like it or not, we move away from our youthful understanding of any music. The interpretive approach changes, not to mention purely technological matters. What is surprising is that looking at it from another angle, discarding something old and stale, you unexpectedly discover music completely new to you. To be perfectly honest, I have to say that it doesn't always happen. Clearly, it happens when a new spiritual, creative basis underpins the old, performers' conception of the piece. When you bring all your experience to the interpretation of the work - professional experience, experience of life, of humanity. For example, nowadays I interpret romantic music quite differently. And it's completely natural. Those vivid, romantic feelings pass, in all of us. There's nothing to be done about that. Q: Do tell us, as a performer, how do you get on with new music. How did it seem to you formerly, and how does it look now? A: In my youth I had an insatiable appetite for new works. I wanted to know as many of them as I could, to play through as many as possible. Now my attitude is considerably calmer. It's hard to say whether that's good or bad, but that's how it is. Of course, it's characteristic of youth to be attracted to everything new, unknown, forward-looking. I must say as a performer, I always 'got on' with new music. In my time I've had works by Gubaidulina in my repertoire. Today, apart from my own works, Six Meditations after Baudelaire and Music for the Millennium, I am playing the 13th sequence by Berio, a very interesting cycle by Kagel' entitled Rrrr, etc. Q: What most attracts Western audiences today - WHAT is being played or WHO is playing it? A: I don't think I'll be mistaken if I answer you like this; in any Western concert hall the person who matters is the performer. The author, that is, the composer, is of secondary importance. But in events of a festival character (especially the more avant-garde sort) it's the other way round - the composer is the centre of attention. Q: Does the policy of Western performers regarding repertoire differ from that of our bayanists and accordionists? A: I think it does. In the first place, Western audiences are not too keen on concert programs 'of indefinite length'. Performers have to take this into consideration. A program will be one part of a concert, or two of not more than 30 minutes each. Audiences are a motley lot, with various tastes and artistic tendencies. And in any case, Western performers try to 'prepare a musical dish' for all categories of listener. Large scale cycles and polyphonic works are very rarely played. Concert programs are frequently constructed from a piquant mixture of ingredients, a kind of repertoire 'soup', so that in a single section you might hear, one after the other, baroque and jazz, avant-garde and music from the shows. Is it a good thing? There could be various answers to that, but as I've already said, one can't ignore the requirements of Western audiences. A performer who does so puts his living at risk. Q: I don't think that many of your colleagues know about the passion you have acquired in recent years for ensemble playing. For instance, in Italy I frequently witnessed successful performances of the Zubitsky Family Quartette, I heard you play with violin, cello, pianio and flute? A: On the subject of ensemble playing, this is not at all a new passion with me. Right at the outset of my career as a performer, my wife Natalia and I played numerous Mozart sonatas, rather successfully I believe, in the Grieg transcriptions for two pianos. Lapinskii's Concerto-Vesnianka was given its first performance by this very ensemble.

Apart from that, after accumulating a suitable repertoire, our joint performances

added to our family income, a matter of no small importance for musicians,

East or West. I have played rather frequently with violinists. My work with

the well known Italian flute quartet, Flutes Joyeuses has given me great

creative joy, both as a composer and a performer.

Apart from that, after accumulating a suitable repertoire, our joint performances

added to our family income, a matter of no small importance for musicians,

East or West. I have played rather frequently with violinists. My work with

the well known Italian flute quartet, Flutes Joyeuses has given me great

creative joy, both as a composer and a performer. Q: What musical material constitutes the basis

of your current ensemble repertoire?

Q: What musical material constitutes the basis

of your current ensemble repertoire?A: In the main, my own compositions in various forms and of various genres - from instrumental miniatures in the style of 'musicals', to such large scale musical frescos as Six Meditations after Baudelaire (bayan and flute) and Music for the Millennium (flute, bayan, cello and piano). The repertoire of our family quartet includes many of my arrangements of the music of such composers as Rachmaninov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Khachaturian, Piazzolla, Skorik and others, principally Slav composers. Q: From the information which often appears on the Internet, I know of your contacts with chamber and symphony orchestras during various festivals. The last one, if I'm not mistaken, was in London? A: Of the Western ones, the most recent was indeed the London Accordion festival. I played my Rossiniana there with the world-famous BBC Symphony Orchestra. In the near future I shall be participating in the annual festival 'First Performances of the Season', here in Kiev. I'll be playing with two of the best Ukrainian orchestras: the orchestra of the Ukrainian National Tele-Radio Company (conductor V. Runchak) and the chamber orchestra 'Kievan Kamerata' (conductor V. Matiukhin). Q: What are you submitting to the judgement of the festival audience? A: With the large orchestra, I'm playing Rossiniana and with the chamber orchestra, Dedicated to Piazzolla. Q: Now, if you've no objection, let's talk a little about your work as a composer? A: I've no objection. Q: So, the year 1975 gave the world not only a brilliant performer, winner of the world cup, but a no less brilliant composer, a representative of the so-called Ukrainian neo-folklore movement (NEOFOL). It was in this year that the triumphal progress of your Carpathian Suite began. In the following years there appeared the two Sonatas, the two Partitas, a whole string of other works for solo bayan. They all became super-popular on all the 'accordion continents'. But touching on the question of your work as a composer I would like to return to 1975. To this day, apparently, not everyone knows that your first major work for bayan was first presented as Skorik's Sonatina, which you played for the All-Union Ukrainian Selection Board, and later at the World Cup in Helsinki. But now the whole accordion world knows this Sonatina as The Carpathian Suite by Vladimir Zubitsky. What made you take the unusual step of concealing the true identity of the composer at this selection? A: Well yes, why should I hide the fact, today I can confirm that such a concealment really did take place. Not in the least as a result of my youthful 'eccentricity', but out of a very mature inflexibility - the conservatism of the overwhelming majority of our bayan masters, who constituted the selection jury. For a young musician to perform one of his own works was considered quite improper, simply impermissible. It was argued that similar licence was not granted to pianists, violinists, or musicians of other specialities. True, it wasn't, but then they didn't need it. The immense repertoire of serious music available to our colleagues who played 'classical' instruments saved them the trouble of any active search for the new, of seeking to broaden the artistic-expressive possibilities of their instruments. The situation for bayanists at that time was completely different. The extremely narrow circle of 'classical' compositions for bayan, especially those in cyclic form, could no longer satisfy progressive young musician-performers. The time positively 'vibrated' with the necessity of penetrating new spheres of imagery, the necessity of conquering new forms with a contemporary resonance, it demanded the creation of a completely new bayan repertoire. Unfortunately, by no means everyone understood and felt this necessity. It was precisely this situation which frequently gave rise to prohibitions, condemnations, unpleasantnesses etc. Remember how the first large-scale works of Zolotariev, later Kusiakov and other composers, were received and evaluated by various highly authoritative musicians. In such a climate, could I, a student at the conservatoire, have put my name on the title page of the Carpathian Suite? It would have meant writing my own death sentence. That's how it came about that (on the advice of Skorik), I concealed my authorship of the work. Q: Whenever did the name of the real composer first become public knowledge? A: Immediately after our return to Moscow from the 'World Cup - 75'. Q: As far as I know, the Carpathian Suite didn't give Mikhail Skorik any peace even after your return from Helsinki? A: Yes, I gave my mentor quite a few problems with that piece. Foreign musicians literally bombarded him with letters after the competition, asking for the scores of the suite and his other works for bayan, although Mikhail hadn't written a single note for the instrument. I had to take it all onto my own shoulders, as the composer, and 'taxi' out of the situation. Q: Yes, the best place for that story would be in the pages of a collection like Musicians Laugh, although in fact there was very little to laugh about? A: Agreed, but I think that by now we can have a smile about it. Q: Do you have your own specific performers, as a lot of composers do, and were you comissioned to write for any particular performers, conductors or publishers in the West? A: When I'm composing, I try not to focus on a specific performer, but I won't pretend that I'm not comissioned to write a work on occasion. When I was still in the Ukraine, I was comissioned to write my Sinfonia-Robusta for bayan and full symphony orchestra by Leonskii, Director of the Serge Kleman Institute of Music and Dance. There were other large-scale orchestral and choral pieces and music for ballet comissioned too. Later, in the West, I wrote my Rossiniana for the 'Virtuosi of Rome' orchestra, and a string of works for the flute quartet 'Flutes Joyeuses'. Recently I've worked closely with the Italian bayan trio 'Vladislav Zolotariev'. Fatum-Sonata, the arrangements of the Carpathian Suite and the Tri piesy of Ligeti were all written for that ensemble. On the subject of works for solo bayan, I've responded to requests from organising committees of various international competitions, and written so-called 'set' pieces. As far as publishers are concerned, numerous solo and ensemble pieces of an educational nature were comissioned by the German publishing house, 'Ralf Jung'. Q: Which bayanist, including those abroad, do you consider the best interpreter of your music for the instrument? A: It's difficult for me to answer that question, because there are rather a lot of performers who play my music for bayan, in the West as well as the East. But of those whom I've been able to hear, I would single out Victor Romanko (Carpathian Suite), Iu.Sidorov, K. Ishchenko (First Partita), Claudio Jacomucci, A-L. Kastanio and Iu. Fedorov (Second Sonata), M.Pietrodarci, K. Zhukov (Second Partita) - I actually awarded him the composers' prize at one competition for the best performance of the First Sonata. Q: I know that, as a composer, you have more than once turned to the balalaika, the bandura, the tsymbaly, you've written for the Ural'skii trio of bayanists, you've written for various folk orchestras. What is the fate of these compositions? Are you continuing to work in the folk-instrument genre? A: Yes, periodically I write for stringed folk instruments. There is a whole range of concert pieces for balalaika, tsymbal, bandura, in my creative portfolio. They are in constant use as concert works as well as educational pieces. The Concerto-festivo for the National Folk Orchestra was created, performed and recorded for 'Kiev 1500'. In their time the Toccata-burletta and Melody in memory of Vladislav Zolotarev were written for the Ural'skii trio of bayanists. Sadly, these last two have remained unheard.  Evidently the complexity of the music, the unusual form and the instrumentation

(the first of these pieces was written for trio, harp and pianoforte) meant

that the works were rejected by the very performers for whom they were written.

After a rather prolonged 'pause', in recent years my creative contacts with

players of folk music for strings have become rather closer again.

Evidently the complexity of the music, the unusual form and the instrumentation

(the first of these pieces was written for trio, harp and pianoforte) meant

that the works were rejected by the very performers for whom they were written.

After a rather prolonged 'pause', in recent years my creative contacts with

players of folk music for strings have become rather closer again.In fact the important Sonata, dedicated to the memory of that great Ukrainian musician, the fine composer Konstantin Miaskov, was written for bandura. My relations with the Russian State Orchestra of the Urals, under the direction of L. Shkarupa, has given me a particular creative joy in recent times. I must mention the extraordinarily high level of performance of this group, with which I recorded a CD. Q: I know that apart from your music for bayan, your choral music is immensely popular, especially the choral concertos, and individul works on canonic texts. To what extent are your major symphonic works involved in the contemporary European artistic processes? A: For me, as a composer, that's a very complicated question. To keep it as simple as possible, I would say that the creative processes taking place today in Western symphonic music are radically different from those of the Slavonic symphonists on whose music I was brought up. The aesthetic of contemporary Western European symphonic writing is very specific; It undoubtedly gives scientific progress a 'shove' in the forward direction (all very interesting from the rational point of view) but in our understanding this music doesn't fulfil its social function. Large scale symphonic works are very rarely written or performed. The following structural plan predominates: the maximum of information in the shortest space of time. Moreover, this doesn't relate only to symphonic works. The classics are the most frequently performed large-scale symphonic works. As for my own symphonic works, well, they're not forgotten in the Ukraine, thank God. The 3rd Chamber Symphony in memory of Liatoshinskii, the Concerto for Violin and excerpts from the opera Chumatskii Shliakh all came out on CD recently in the USA. Q: Tolstoy once said that a writer should only write what he can't not write. If those words hold true for composers, it seems to me that that is precisely how you write for bayan. I know that you're not in the least troubled by the quantitative indicators in this field. Nevertheless, you've re-fueled your 'Italian period', as you've already said, your creative mine of new works for the bayan. Do tell me about them? A: First of all, the two concerti for bayan and orchestra belong in my 'Italian period'. I mean Rossiniana and Piazzoliana. These are rather large-scale, expansive three-part works. Both exist in several of my own arrangements: Rossiniana - for bayan with chamber orchestra, for bayan with full symphony orchestra and, finally, for bayan and pianoforte; Piazzoliana for bayan with chamber or accordion orchestra. I think I should include here Music for the Millennium and the above-mentioned sonata for trio, Fatum-Sonata. Apart from which there are numerous small pieces for solo bayan, and for bayan with various instruments and ensembles. Q: Are these works in the repertoires of other performers, are they published? A: S. Voitenko and S. Schappini are among the performers of these works. Unfortunately, the circle of performers of my most recent important works is so far limited. The reason is very simple and banal - the absence of scores. Q: So they're not published? A: They all exist in the original computer version, but they have not yet been published with a large print run. If any colleague is interested in my latest or earlier works, the scores may be obtained from the address given in the advertisement on the last pages of 'Narodnik'. Q: Acquainting myself with your latest works (and not only those for bayan), I was struck by the 'grudging' expenditure on colourful-expressive means, a growing restriction in their selection, the desire to show the inner workings of the musical material (one involuntarily remembers the words of genius, written by Goethe, that one can recognise a master by his self-imposed limitations). Is it like that? Is it true that maturity, for the artist, consists in sacrificing his ability? A: I try to use the exact amount of material which is essential to the embodiment of this or that idea. Neither more, nor less. Of course, in his youth, a composer's talent most often reveals itself in a multitude of colours, in the generosity of his melodic inventiveness, the fire and irrepressibility of his artistic fantasy, leading at times to excess. In other words, youth is an inexhaustible store of creative energy etc. Later (and this evidently happens to any composer) comes the deepening of thoughts and feelings, the ability to discern the sharply-conflicting, dramatic aspects of being, and to express them in sound. To cut out more and more ruthlessly those effective details, elements, frequencies, which are not an intrinsic part of the architechtonics of the whole, which do not flow from the logical development of the musical idea. Q: It's hard not to agree with that, but it seems to me that the artist reveals his maturity not only in his skilful work on the material, but in his choice of that thematic material, in its philosophical interpretation? A: Any true artist will always turn to the eternal themes: life, death, love, joy, suffering etc. these themes are determined by the very nature of art. But as far as the maturity of the artist is concerned, genuine maturity, in my view, comes to him when he fully understands mental suffering, grief and pain. He cannot acquire spiritual riches without such understanding. One of the great masters said that to create a truly significant work of art one must have talent, a mastery of one's craft, and a wounded heart. Q: Have you any edifying advice to young composers working in the field of music for the bayan? A: Looked at from the position of our complex, crisis-ridden or, as it is euphemistically called, transitional period, that's not a simple question. But in spite of that, I appeal to my young composer-colleagues, especially former bayanists, who know the nature and the rich palette of expressive means that our instrument possesses, not to abandon the bayan; its possibilities for the composer are by no means exhausted. Especially in relation to chamber and ensemble genres. And, equally, to light music, jazz and folk music. I firmly believe that the bayan-accordion art has a great future, in all its manifestations and directions. Q: Vladimir. I think we will be doing you an injustice if we don't include one further sphere of activity in our conversation - your musico-social work? A: Musico-social activity has always occupied a significant place in my creative life. It has meant that I always find myself in the thick of events, in touch with things, both on the creative and the social level. A lot of my time and energy has been devoted to the Ukrainian Association of Bayanists and Accordionists, of which I was president for about ten years. Q: As far as I recall, it was you yourself who conceived the idea of organising such an association under the auspices of the National All-Ukraine Musicians' Union? A: But you know, I only sounded out the idea, so to speak. In 1989 the time itself demanded the organisation of an independent creative structure, which could gather together and unite Ukrainian bayanists, composers and teachers under their own standard. It was necessary to make a sober evaluation of what had been achieved, cut out everything superfluous, to plan the main path of development for the Ukraine's women accordionists. We managed to hold two large scale international festivals, four 'Krivbass' international competitions, and run several scientific-practical conferences etc. Q: It would be fair to say that the first real break-through of Ukrainian bayanists into the international arena is connected with the name of the Association? A: Of course, how could you forget 1991, when for the first time, (even before the collapse of the Soviet Union) a Ukrainian delegation consisting of - apart from you and me - four performers in various age categories took part in the 'World Trophy' in Spain, in Kuenka. As a result, for the first time the trophy was held by the Ukraine. That was only the beginning. Q: It's pleasant to remember, but all the same, let's return from 1991 to the present. Knowing your current many-faceted 'polyphonic' structure of activities, I'd like to ask you one more question. One knows that many venerable musicians, here as well as in the West, hold their festivals, competitions, seminars, etc. In other words, they appear as supervisors, artistic leaders of the above-mentioned musico-social activities. For example, such greats as Rostropovich, Krainev, Spivakov and others. As far as I know, even you have not avoided this fate. Such international competitions as the 'Priz Monteze' and the 'Priz Lanchano' are held today in Italy under the patronage of Vladimir Zubitsky. Do tell us something about them? A: You know, it's true that festivals, competitions and other cultural activities take place under the patronage of those great musicians you mention, but as far as I'm concerned, you're making rather too much of it. I'm not the patron or the artistic director of the above-mentioned or any of the other numerous competitions.

Q: Do members of the former Independent Republics take part in your competitions? A: Of course. I can name many, many bayanists from the Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, Belorussia, the Baltic countries etc. As a rule they are all very well professionally prepared, that is, the schools are of a good standard, but their instruments (especially in comparison with Western competitors) leave a lot to be desired. This is particularly so in relation to children's instruments. Q: How is the question of financing Western-European competitions for performers decided? Is there an existing structure of state support? A: Apart from the fact that the West is, of course, wealthier, the question of finance for culture, education, science and the other humanities is extraordinarily complicated. If we're talking about the material basis for performers' competitions, it certainly does not rely on government structures. At best town councils will provide their share. Everything else is a matter of backers, sponsors, other private firms interested in advertising their products during the competition, and of course the fees of the competitors themselves. I don't know of any other schemes for financing such competitions. It's hardly likely that they exist. Q: As a member of the jury for many international competitions, I presume that you're very well informed on the young performers of today, on their strengths and weaknesses? A: Above all, from my point of view, the young people of today who take part in international competitions do much to correct the preconceptions of what is and what is not characteristic of their age-group. More and more frequently one sees tenacious, persistent, purposeful young people, with a maturity beyond their years. They rely not so much on good fortune, luck or chance, as on themselves. Evidently it'a a sign of the times. That's what dictates its own laws, that's what produces today's mature young people. It seems to me that this is a positive moment. This is undoubtedly the source of the huge growth in the technical ability of these young competitors, the pushing back of boundaries in the repertoire, the vitally important introduction of new works. On the negative side I would put the egoistic aspects which are now so widespread. Q: Egoistic? A: I mean those young competitors who provoke the audience and the members of the jury to a heightened emotional reaction by the way in which they conduct themselves on the platform. They behave affectedly, roll their eyes, keep tossing their heads, they 'feel intensely', they 'live the music' etc. As a rule, these intense feelings don't spring from the music but from quite other 'stimuli'. I am convinced that a musician who is completely absorbed in creativity, in the interpretation of a work, is not going to attract that excessive amount of attention to himself. He doesn't grimace, he doesn't overwhelm the audience with hypertrophic emotionality. Q: You mean, if I understand you correctly, the artistic egoism of youth consists of an excessive concentration of attention on itself, on its 'I', with all the creative and very far from creative consequences? A: Absolutely true, although it's not a simple problem. You can understand that to limit your 'I', consciously, to make it of secondary importance on stage - it's not an easy thing to do. Really, it means going against your own nature, and, as you know, nature will resist. For this reason, however parodoxical and contradictory it may seem at first sight, I would answer you like this: If I say categorically 'no' to artistic egoism (in its worst manifestations), then at the same time I am categorically 'for' the personal basis of the performer's art (in its positive sense). I consider that the greatest and most honourable victory is not victory at some competition or other, but the victory over ones own self-love. But as a rule musicians achieve that victory only in maturity. It is experience which matters, and in the process of acquiring experience one is constantly tormented by the thought: 'I am in a performing art.' Q: In the previous question I made a point of mentioning the far-from-creative consequences of the performing egoism of certain young people. Unfortunately we are witnessing, more and more frequently, that extremely unpleasant phenomenon, 'fake-laureatism'. I think you know very well of what - and even of whom - I'm speaking. This sort of egoism is verging on the criminal. The most staggering thing is that with the aid of total and vociferous self-advertisement (which requires, as you know, substantial resources), newly-made 'champions' and 'victors' achieve their objective - they are awarded honorary titles, respected professors and mentors hastily add their names to their professional list of important persons and to every possible directory. Do similar things happen in performing circles in the West? A: I think not. State-awarded honorary titles, as we understand them, simply don't exist in the West. As for these 'home-made' laureats, they don't turn up when the matter is to be determined - the main thing, the mastery of the musician. The highest possible title is the NAME of a man, his reputation as a performer. If you're talking about 'fake-laureatism', then I can guess whom we're discussing. It seems to me that mentioning his name here would be doing this 'well-known figure' too much honour. Of course, these fellow-travellers and musical 'Ostap Benders' are no ornament to our calling, even if they appear as the possessors of non-existent gold and platinum lyres (according to them, the special prizes of the World Confederation of Accordionists), even if they have been awarded honorary titles. I am convinced that time and God will put everything in its place; the time will come when these 'flights of fancy' are investigated. Q: Vladimir. I am sincerely grateful to you for such a wide-ranging and fascinating conversation. In conclusion, in the name of the editors of 'Narodnik', the National All-Ukraine Union of Musicians, the Ukrainian Association of Bayanists and Accordionists, may I express the hope that next year, which will be your jubilee year, we shall meet again on our native Ukrainian soil, and may I wish you and your musical family a long, rich and fruitful creative life? A: Thank you very much, Anatolii, for an immensely enjoyable couple of hours together, for a conversation which wasn't all that easy for me, and for your good wishes. Finally, I wish all our colleagues, and the readers of 'Narodnik', great flights of creative inspiration and a firm belief in the happy future of our folk-instrumental art. Till we meet again.

Q: How did you first start or become involved with the accordion? A: All my family were medical workers and played the folk instruments. Father played mandolin, balalajka, bayan. My older brother at the beginning played diatonic accordion and after that played bayan as well, so, from the age of three I played on "bubna" (Ukrainian folk instrument) in the "family trio". Q: Why did you choose the accordion rather than another instrument? A: My father played the bayan, it was his favorite instrument, and father was for me a big authority. Also, bayan was the most popular and the most obtainable instrument in the town were I lived. Q: Tell us a little about the town where you were born and where in Russia is it located? A: I was born in the south of Ukraine (Ukraine is south from Russia), in the little colorful village on the river Dnestr called Goloskovo. However, I spent my childhood in the town of Znamenka which is a small railway town in the central Ukraine area, full of lakes and forests. Q: What role did you parents play in your early music education?

A: My fathers dream was to become a professional musician, but the war prevented him. That is why he tried to realize his dream through his sons. Mother, as many Ukrainian women, loved to sing Ukrainian folk songs. All my childhood was surrounded with music. Q: Tell us about your early teachers? A: My very first teacher after my father, was a blind bayanist who taught me to play by ear, (watch his fingers), without music. After that, my teacher was another bayanist who was conducting an amateur bayan orchestra - Alexandr Usatjuk - he was in love with the bayan and the poetry. Because of him I started to love the bayan as part of my body without which you cannot live. From the age of six I was already working as an accompanist to the choir and soloists in the pioneer camp, and I was also singing with my own accompaniment. Afterwards, our family moved to the big industrial town of Krivoj Rog where I studied at the high school of music in the class of Nikolaj Potapov. He was the first one to give me professional skills (everyday practicing scales, arpeggios, etudes) to introducing me to the free bass bayan which was a big novelty in those days. Q: Any humorous memories of those years? A: At one of the first performances of my orchestral work (I was still a student at the conservatorium), one orchestra player started playing his part later then needed (it was the percussionist, playing the baraban), so when the piece finished he was still playing his part. Realizing that the conductor had already put his hands down and the whole orchestra stopped, he started to play softer and softer and faded eventually. But suddenly his colleague - a tuba player yelled "Finish Vasja, we are already there!" It was my first success and first shock from worry for the faith in my own "child". Q: Did your early teachers have any musical points on which they made particular emphasis that you still remember today? A: Yes. For example, they said, that very often it is more important to be silent than to talk. In the communist time that was a rule in order to survive, but the truthfulness of this still applies today. Q: Tell us about your tutors at the Gnessin college in Moscow and the Kiev Conservatory and your studies at these institutes? A: To my sorrow, my teacher N. Potapov suddenly died young and I went to study in Moscow at the famous secondary music school "Gnessinih" in a class for composition and a class for bayan. My tutor Vladimir Motov was wonderful person as well. The classes included improvising, composing and analyzing. There I got involved with composing, thanks to my teacher who asked me to bring to each lesson variations on a given theme. It was very consuming, interesting and not hard at all. As a result my tutor Vladimir Motov made a text-book about improvising on the bayan. Up to this day, my old Moscow teacher has remained my best friend and advisor. I graduated Conservatorium of Music in Kiev, Ukraine, where I was fascinated with the phenomenal musician, concert soloist - Vladimir Besfamiljnov. It was his tuition who brought me to the top in performance on the bayan. Parallel, I graduated in 1977 as a composer at the Kiev Conservatorium (in the class of the well known Ukrainian composer - Miroslav Skorik) as well as opera and symphony conducting (in the class of Vadim Gnjedash). I am glad I had such a teachers. They opened up a musical world for me, without which I cannot imagine how my life would be. Q: When and why, did you decide to make music your career?

A: It happened by intuition during my early childhood, when I was "breathing" music like the air. Gradually music become a part of me. Even hard professional work didn't kill that love. Q: One of your major international competition successes was at the Coupe Mondiale in 1975. How important do you feel that success was for your career? A: Straight after the victory at the international competition, I was give the opportunity to perform 40 to 50 solo concerts a year in all the areas of the former USSR. That was a really good point of the social system. Now days, the winners of the international competitions have to organize their concerts themselves. Q: You have been an adjudicator at international competitions, and also a competitor. What would you say are the strengths and weaknesses of such competitions?  A:

Of course, defeat - it is always a shock, physiological breakdown. But my

teacher Vladimir Besfamilnov was always saying - " The main thing is

not to win but to play your best ". That way worries about yourself

are transmitted to the worrying about the musical piece being performed. A:

Of course, defeat - it is always a shock, physiological breakdown. But my

teacher Vladimir Besfamilnov was always saying - " The main thing is

not to win but to play your best ". That way worries about yourself

are transmitted to the worrying about the musical piece being performed.

Q: How has your musical career impacted on your personal life? A: I started performing my first solo concert with the lady pianist who eventually become my wife and gave me two sons who are also musicians. Q: When were your first professional concerts? A: It is hard to say. When I was a student, I was taking part in various concert with a great pleasure. I was traveling as a "demonstrator" to the methodical conferences with a lot of bayanist, professors. Especially, I remember traveling with the Kiev bayanist Ivan Jashkevich, very well known for his transcriptions for the bayan - to Siberia and to the Urals (Russia). Perhaps, my first very important concert was in 1975, after the victory at the international competition, in the Hall of the Kiev Philharmonic. The hall was packed and the success was enormous - I will remember it for the rest of my life. Q: When did you first tour outside Russia and to which countries? A: In 1972 to Czechoslovakia. Q: Would you tell us about your recent tour of China? A: Their tradition left a very big impression on me - musical tradition as well as the general cultural tradition of their country. I was also very impressed with the little kids (aged 10 to 12) who played very complicated pieces on the stradella (standard bass) piano accordion. For example: Listz's Rhapsodies! China is also making very large and fast cultural and economic progress. I hope, they will let us know more about themselves soon! Q: Is there any teacher or artist to whom you would like to pay particular tribute, for their inspirational effect on your musical career? A: Yes, I am very grateful to all my teachers who gave me their talents. There is a saying : students are not grateful ! But I am full of gratitude to all my teachers live one as well as one who passed away. Q: Do you have any family and do they share your interest in music? A: Yes, my wife, Natalia is a pianist, my sons Stanislav and Vladimir - flute player and cello player, they also study composing. We often play all together, family quartet at home as well as on stage. We play a lot of transcriptions of Russian and European classical music, jazz and Piazzolla. Our family life is - all music! (Our poor neighbors!) Q: What non accordion music do you most like to listen to? A: I love all good music, no matter the instrument including Bulgarian and Rumanian folk music, professional classical, jazz, contemporary...... Q: You have conducted a lot of courses and seminars for accordionists? What subjects do you believe are important and why? A: 1. Everyday technical exercises (scales, arpeggios, etudes) are also needed as training for sportsmen. 2. Physiological freedom and relaxation of muscles and breathing. Otherwise everything achieved at the lessons gets blocked. Q: List some of the most interesting and important venues you have performed at. A: Premia UNESCO for the composition " REKVIEM - Seven Tears" in 1985. Performance of the second Symphony with the Ukrainian State Orchestra in 1979. Tour in the USA in 1996. My first CD. My choir concerts in Moscow in 1990. Q: Describe your most "incredible" or "unusual" or "interesting" performance situation? The most humorous? A: During a town concert with an accordion orchestra in Italy, one drunk man came up to me and tried to hit the right side of my bayan with his fist. So I had to, keep changing leg positions so "I could miss his hit" while not stopping the performance. The audience loved the sight of it! Q: Could you tell us how you first became interested in composing? A: From early childhood, I loved to improvise. Often it was outside on the street next to our house, where the neighbors were getting together to "listen to the bayan" . After that I wanted to put in writing some interesting simple musical thoughts. From there it started. Q: Describe the first pieces you composed? A: It was the "Polka" of 12 bars. The first audience of the 6 years old "vunderkind" were two old ladies and the stray dog on the street. Q: Is there any composer who has particularly inspired you? A: Yes. It was Schostakovich, Bartok, Skorik, Stankovich. Q: Do you have melodies running around in your head waiting to get out? A:Yes, that often happens during my sleep. I am conducting my new, not even written symphony....but when I wake, it is all gone - there are only memories about the orchestrating - some sense of unhappened happiness..... Q: When composing do you compose a melody and then add the harmony OR do you compose a chord progression and then add the melody? A: Normally, a professional composer is hearing with the "inner hearing" all the "musical verticals" - from the melody to the harmony and even the orchestrating (like Mozart or Schostakovich ). I never divided the music into the melody and the harmony. For me it is one whole, like parts of the human body. Normally, music comes to me as I am moving i.e. on the bicycle, on the bus. .. Beethoven and Tchaikovsky were composing while walking, writing on the spot their main thoughts. Schostakovich, on the contrary, wrote only while sitting at the table, and was saying that his "thoughts are on the sharp top of his pencil, and one note drags another one" - "and so on, until there is a finished piece". Generally, composing was always a big mystery. Many composers like : Stravinsky, Prokofiev, composed only with the piano. Touching the piano keyboard and sensing it was inspiring to them and they, improvising, were showing all the most interesting melodic and harmonic combinations. I think, the most important - is to leave a little bit of your soul in your music. I remember when I was a student, Khachaturian asked a first question to any student: " If I change your score, would you be crying ?".... In the contemporary avant-garde, where the main criteria is "is it interesting or not ?", emotions play the last role. This could be the reason why some pieces are heard only once or twice, as one-day-hits, and after that they die out. Q: Which of the works that you have composed, do you like the best? (Please tell us why.) A: I think, you love these compositions to whom you gave the most of your soul. For me it is the third Chamber Symphony in the memory of B. Ljatoshinsky and Choir Concert "My Hills". As all the parents who love their newborn the best, I am also finishing now my Concerto to the memory of A. Piazzolla for the bayan and orchestra and I am worried for its faith, as for the venerable child whose whole life is only beginning. Q: You have composed for other instruments besides the accordion, how did this come about? A: When I was starting to study at the department of symphonic conducting, I came to love symphony orchestra and its instruments. Musical drama can sanitize all kinds of art, and was always very interesting to me. That is how I started writing opera, ballet, symphonies. Q: Which instruments do you prefer to compose for in combination with the accordion? A: Woodwinds are blending in well with the bayan, contrasting instruments : harp and piano beautifully fulfill. I love a combination of the symphony orchestra and powerful bayan "Jupiter". In the Russian music, from Zolotaryov there is tradition of the bayan as a symphonic instrument. In the west, the bayan is normally taken as a chamber instrument. That is why, some western accordionists have of late, refused to perform organ pieces on the accordion, and are performing only harpsichord works, with the explanation that the "bayan is a little instrument". I am categorically against it. The bayan is a powerful philosophical instrument, able to express big ideas as well as very quiet delecate sounds and chamber sounds. The bayan is prophet of its own kind, as a organ or orchestra. Q: Do you have any favorite composers for instruments other than the accordion? A: Yes. From the " old" composers I love J.S.Bach, Schuman, Chopin and Rakhmaninov. From the modern ones I love Bartok, Stravinsky, Liatoshinsky, Stankovich. Q: When did you record your first LP, CD or cassette? A: I started recording at the Ukrainian Radio while I was still a student. I played music of the Ukrainian composers, transcriptions for the bayan. My first LP I recorded in 1975 after the international competition, where I included fragments from my own compositions (Sonatina, Children Suite No1). Q: Where can readers purchase your recordings? A: Write to me: zubytskyy.v@provincia.ps.it (You can see a list of compositions and CD's and the works contained on each CD at http://www.accordions.com/zubitsky ) Q: You have often recorded with other instrumentalists. Which non accordion instrument/s did you feel most effectively complimented the timbre of the accordion? A: Bass clarinet, cello, flute. Q: What is your favorite, of all the CD recordings you have made and why? A: Could be Beethoven Variations on the Russian Theme or some jazz pieces from the CD No 5 - they turned out the most natural. Q: Do you know which of your CD's has achieved the most sales? A: CD No. 4 with the folk music and hopefully CD No. 5 with the jazz and light music. People like to be entertained, and of course, classical pieces cannot compete with the entertaining ones in the commercial terms. But, each genre finds its audience. Q: What other interests and hobbies besides music do you have? A: I love fishing. At one critical point, my father made me burn all my fishing gear, and if didn't do it, I would have become a fisherman and not a musician. If I am lucky to find 1 or 2 hours to spend on the river - for me that is the biggest happiness and the best rest. Q: What do you regard as your greatest musical achievement? A: Premiere in the year 2000 of my "Symphony - Rekviem" Ocean of the destanies for the bayan, choir, soloists, big symphony orchestra in the North America. Q: What are your future career objectives and where do you see your career progressing? A: We have alot of plans, but whether or not they all eventuate is known only to God. |