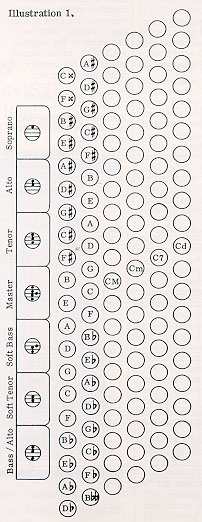

The standard stradella button keyboard, either alone or as an integral part of expanded systemizations which incorporate free bass as well, demonstrates a stylistic viability which is reflected in vastly different approaches to musical composition for accordion. Composers continue to draw on the standard stradella system's resources, sometimes extracting new possibilities or realizing latent potential. Recognition and use of these possibilities demands imagination and a practical application of information about the following:  1. Range of the single note buttons. 2. The inversions produced by the fixed chord buttons. 3. And the characteristics of the various registers. These offer challenges that not all composers and transcribers have been able to meet. Few have recognized the full musical potency there, but additions to the repertory of very interesting substance and the system continue to interest the performer and composer alike. In Galla-Rini's Concerto for accordion and orchestra, written in 1941, and in many of his transcriptions, complete and consistent application of the musical resources of the standard stradella keyboard are in evidence. These works abound in effective and idiomatic writing for the left hand, which must be carefully studied by every serious student of the instrument. Continued widespread use of the stradella system and the music associated with it is enough to warrant attention. The analysis set forth in this article, of the registers in particular, is necessary information, not only for the composer and arranger, but for the teacher, student and performer as well. THE BUTTON KEYS.The standard stradella keyboard consists of 120 buttons - six parallel rows of 20 buttons each, graduated on a rising angle - which are functionally divisible into two sections.The two rows (mediant and fundamental) adjacent the switches produce 12 different single notes, the remaining 28 buttons in these two rows are duplicated for facility in fingering at different keyboard locations. (Use of the thumb is rarely practicable.) The buttons of the next four rows produce fixed chords 12 each of major, minor, dominant seventh (fifth omitted), and diminished (triad). The correct note content of the latter may be arrived at by spelling a diminished seventh chord, letter named according to the row in which it is found, and omitting the fifth. The remaining eight buttons in each row again provide duplications for ease of fingering. THE SWITCHESThese Switches are the mechanical levers which effect changes of reed couplings. Standardized combinations of the reed sets are indicated by the switch symbols (see illustration). Each space within the circle represents a difference of one octave. Reeds are open

and operative when a dot appears on a given space or line; inoperative (closed)

when that space is empty. The middle line denotes the set of reeds (contralto)

which doubles the pitch of the upper half of the tenor and the lower half

of the alto reed sets.

within the circle represents a difference of one octave. Reeds are open

and operative when a dot appears on a given space or line; inoperative (closed)

when that space is empty. The middle line denotes the set of reeds (contralto)

which doubles the pitch of the upper half of the tenor and the lower half

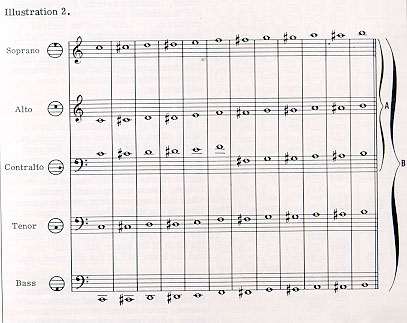

of the alto reed sets.According to the register in effect, single notes will be affected by changes in basic pitch location and octave duplication; chord buttons by various inversions, pitch levels and octave doublings. THE STANDARD SETS OF REEDSA set of reeds may be defined as a chromatic sequence of single reeds equal in number to the semitonal content of the immediately available range of a keyboard (measured by the single note button range in the case of the stradella keyboard).For the standard stradella keyboard these sets of reeds consist of 12 semitones (one semitone short of a complete octave). These reed sets are, with the exception of the tenor and bass sets which can only respond for the single note buttons, shared commonly by both the single note buttons and the fixed chord buttons. In other words, any set of reeds which is open (as represented by a dot in the symbol) will respond for the single note buttons as shown by the long bracket (marked B) in illustration 2; the short bracket (A) indicates the upper three sets of reeds - soprano, alto and contralto - which, if open, respond for the chord buttons. Illustration 2 shows the sets of reeds for the standard stradella keyboard together with the symbols representing each specific set of reeds. With the exception of the soprano set, these sets of reeds are not usually available uncoupled.  The

symbols which represent the seven standard reed coupling combinations are

pictured at the left. The

symbols which represent the seven standard reed coupling combinations are

pictured at the left.THE SOPRANO REGISTERThe Soprano Register is the highest pitched octave of the standard left hand keyboard. The uncoupled soprano set of reeds (c'' to b'') will respond for both the single note buttons and the fixed chord buttons. The latter will then produce chords with pitches and in positions consistent with these tones.The switch symbol for this register shows a dot in the space representing the soprano set of reeds (see above), indicating that this set is operative, while the empty spaces indicate that the other sets of reeds are closed. Example 1 shows the pitch and range of the single note buttons and that of the fixed chord buttons are the same. Example 2 illustrates the positions and pitch of the C and B chord buttons which will result accordingly in the Soprano Register. The Soprano Register's reeds are small and may be easily overpowered by the right hand keyboard. Relatively little dynamic strength (volume) is possible. Careful attention to the registration and substance of the material played on the right hand keyboard is necessary to avoid obscuring the left hand keyboard's performance in this register. Infrequently encountered in accordion literature, the Soprano Register is usually not available in any but professional model instruments. Student accordions generally do no even contain the required set of reeds. However, the Soprano Register can be very effective and its use by composers should not be discouraged. Notation for this register is not always given at pitch. Although notation at pitch, or at least not more than one octave lower than sounding, should be recommended. Bass clef notation may be found as much as three octaves below the actual pitch. Chord buttons are often indicated by an abbreviated notation - root and chord symbol (single note notation). [The musical examples throughout this article are given with notation for the left hand at pitch. In the case of octave duplications, according to the lowest sounding set of reeds. Fixed chords are given in full (unabbreviated) notations.]  Example 3 is an excerpt from Ernest Krenek's Toccata (1952). The single

note buttons of the left hand are exploited to good advantage in the Soprano

Register. Excellent balance between the left and right hand key boards is

achieved through the use of the Ottavino (piccolo) Register of the right

hand keyboard - the reeds being similar in size to those of the soprano

set which is indicated for the left hand keyboard.* Notice in the last measure,

the continuation in pitch of the left hand part, by the right hand which

sounds one octave higher than normal treble clef notation.

Example 3 is an excerpt from Ernest Krenek's Toccata (1952). The single

note buttons of the left hand are exploited to good advantage in the Soprano

Register. Excellent balance between the left and right hand key boards is

achieved through the use of the Ottavino (piccolo) Register of the right

hand keyboard - the reeds being similar in size to those of the soprano

set which is indicated for the left hand keyboard.* Notice in the last measure,

the continuation in pitch of the left hand part, by the right hand which

sounds one octave higher than normal treble clef notation.Example 4 shows the application of the chord buttons in the Soprano Register, which is relatively rare. In Prelude (1971/rev. 1972) by Donald Balestrieri, a 12-tone series is verticalized. Notes from both hands often overlap. The simultaneous four notes in the left hand at each of the last two measures is accomplished by combining two chord buttons with two notes in common. However, since the single note buttons are also operating the soprano set of reeds, the same aural result could by be obtained by use of single note buttons alone or by combining certain chord and single note buttons. THE ALTO REGISTERThe alto set of reeds is pitched one octave lower (c' to b') than the soprano set of reeds. A coupling of the alto set of reeds with the soprano set of reeds constitutes the Alto Register. Both sets of reeds will respond for either the single note buttons or the chord buttons.It is, however, the alto set of reeds, being the lower octave of the coupling, which establishes the basic pitch of this register. Both the single note buttons will then generate upper octave duplications via the soprano set of reeds, but the basic pitch is established by the alto set of reeds. The switch symbol for this register shows dots in the spaces representing the alto and soprano sets of reeds (see above), which indicate they are open while the others are silent - clearly illustrating the octave relationship between the two sets of reeds.  Example

5 shows that the alto set of reeds (whole notes) coupled with the soprano

set of reeds (diamond notes) will be operative for both the single note

and chord buttons. Example

5 shows that the alto set of reeds (whole notes) coupled with the soprano

set of reeds (diamond notes) will be operative for both the single note

and chord buttons.Inversions of the various chord buttons will be the same as in the Soprano Register, albeit one octave lower, since the range for determination is also from C to B. Since, as with the Soprano Register, the sets of reeds which are open will respond for either the single note or fixed chord buttons, the chord buttons will produce inversions and pitches consistent with the range and pitch of the single note buttons. Example 6 demonstrates the C and B chord buttons. The upper octave duplications by the soprano set of reeds (diamond Notes) could be taken for granted in notation and they are, in any case, implied by the dot in the upper space of the register symbol. The preferred notation would usually be at pitch (in the treble clef) or at least not more than one octave lower (in bass clef). However, this register may be found notated in the lower part of the bass clef staff as well. Chord buttons are often given in abbreviated notation (root and chord symbol). Example 7 is a passage from Felice Fugazza's Danzi di Gnomi (1959), in which the alto Register's single note range is utilized for the lower part in a three-voice episode. Example 8, a quotation from Anthony Galla-Rini's transcription for accordion solo of the Rhapsodie Espagnol by Liszt, will illustrate the rarely encountered pitch relationship between the single notes and chord buttons in the Alto Register. Some curious writing for the left hand keyboard has sometimes resulted from an apparent failure to comprehend the fact that the same set of reeds will respond for both the single note and chord buttons in the Soprano and Alto Registers. In these registers, should a chord button be depressed along with single notes which are already members of that chord (or added after the chord button is depressed) the single notes in question will prove of no aural purpose. Reeds which are already sounding for a chord button cannot, at the same time, be duplicated by single note buttons, or vice versa. The opening measures of Otto Luening's Rondo for accordion solo illustrate such an instance where the single note buttons can be omitted without resulting in any audible change. THE TENOR REGISTERhe basic pitch level for the single note buttons in the Tenor Register is established by the tenor set of reeds (c to b) which is the lowest sounding. These are coupled to the alto and soprano sets. Since the tenor set of reeds cannot respond for the chord buttons (see Illustration 2), it is the alto set of reeds, being the lowest sounding set activated for the chord buttons, which will establish the basic pitch level and determine the inversions of the chord buttons in this register.Attention should be drawn to the fact that only in the Tenor Register is there no break in the basic pitch continuity between the single note buttons and the range for determining the chord buttons. The practical significance of this will be pointed out in a successive example.  The three octave voicing of the single note buttons is graphically illustrated

by the switch symbol (see above), showing that the soprano, alto and tenor

sets of reeds are operative. The silence of the tenor set for the chord

buttons must be understood.

The three octave voicing of the single note buttons is graphically illustrated

by the switch symbol (see above), showing that the soprano, alto and tenor

sets of reeds are operative. The silence of the tenor set for the chord

buttons must be understood.Example 9 shows the reed sets which operate for the single note and chord buttons in the Tenor Register THE SOFT TENOR REGISTERExample 10 illustrates an alternative voicing - Tenor (piano) - available for the Tenor Register. With it, a more subdued effect is achieved by eliminating the soprano set of reeds. Thus, the basic pitch of both the single note and chord buttons remains undisturbed; the single notes will now sound in octaves (tenor/alto) and the chord buttons undoubled (alto).The sets of reeds for Tenor (piano) Register are shown in the switch symbol. Because the tenor set of reeds cannot respond for the chord buttons, they will sound exactly the same in the Tenor (forte) Register as in the alto Register - with the soprano and alto sets of reeds responding for the chord buttons in octaves (refer to example 6). The chord buttons in the Tenor (piano) Register will yield pure, uncoupled chords since the soprano set of reeds is silent and only the alto set will respond for the chord buttons. Example 11 lists for comparison, the C and B chords as they will sound in the Tenor (piano) Register. A decided increase of strength over the previously discussed registers is evident in the Tenor Registers because the reeds of the tenor set are larger. This alleviates some of the more delicate problems of balance mentioned in connection with the Soprano and Alto Registers. Notation is in the bass clef, sometimes one octave below the actual basic pitch. Chord buttons are often given in abbreviated notation. It is sometimes convenient to notate the single note and chord buttons one octave lower using either the ottava alta sign (8 - - - -) or the clef alta sign (####). Example 12 is a melodic excerpt from the Alan Hovhaness Accordion Concerto - Opus 174, played against an aleatoric background of multitudinously divided strings, which falls within the single note compass of the Tenor Register. The Tenor (piano) combination, sounding in octaves, is used; the unison doublings of the right hand add strength and solidity.  Example 13 shows application of chord buttons in the Tenor (piano) Register

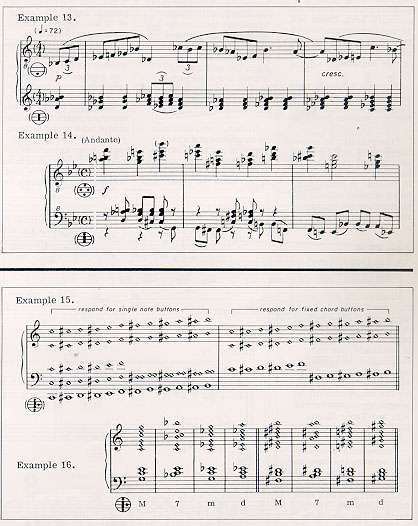

in an excerpt from Paul Creston's Fantasy for accordion and orchestra, Opus

85. Note the following points: firstly, the left hand accompaniment is consistently

above the melodic line which has been assigned to the right hand in a low

register. [The right hand will sound one octave lower]; secondly, each of

the four note chords beginning at the penultimate measure of the example

is achieved by combining two chord buttons which have two notes in common.

Example 13 shows application of chord buttons in the Tenor (piano) Register

in an excerpt from Paul Creston's Fantasy for accordion and orchestra, Opus

85. Note the following points: firstly, the left hand accompaniment is consistently

above the melodic line which has been assigned to the right hand in a low

register. [The right hand will sound one octave lower]; secondly, each of

the four note chords beginning at the penultimate measure of the example

is achieved by combining two chord buttons which have two notes in common.Example 14 demonstrates an application of the continuity in the basic pitch between single note buttons and that of the fixed chord buttons. Here, in a transcription for accordion and orchestra by Donald Balestrieri of Liszt's Prelude and Fugue on the name of Bach, the melodic shape of the left hand part has been preserved by being passed between the single note buttons and the lowest notes of the chord buttons. The upper harmony notes of the chord buttons unobtrusively double those in the right hand. Note that the left hand part will sound one octave higher than usual bass clef notation and that the right hand part will sound one octave lower than usual treble clef notation. BASS REGISTERSThe Bass Register is established when the bass or lowest-sounding set of reeds (C to B) is operative for the single note buttons.Three different reed set combinations are available in the standardized systemization. They are shown and described in the following paragraphs THE MASTER REGISTER (BASS FORTE)All five sets of reeds - soprano, alto, contralto, tenor and bass - are open as shown by the five dots which mark the switch symbol. The contralto set of reeds is the lowest sounding for the chord buttons and it establishes the basic pitches for the fixed chords, while the bass set of reeds determines that of the single note buttons.Example 15 shows which reeds are operative for the single note and chord buttons. Here, as elsewhere, the blend of these upper octave duplications with the fundamental, pitch establishing set of reeds, is such that it is hardly more than amplification of the basic overtone series. Example 16 illustrates the sound of the chord buttons, given again for C and B chord rows, for comparison. THE SOFT BASS REGISTER (BASS PIANO) Example

17 illustrates the bass set of reeds coupled with the tenor and contralto

sets. These will respond for the single note buttons; the contralto alone

responds for chord buttons in this register. Example

17 illustrates the bass set of reeds coupled with the tenor and contralto

sets. These will respond for the single note buttons; the contralto alone

responds for chord buttons in this register.Example 18 shows the contralto reed set, which responds for the chord buttons, without doublings. This register is exceedingly useful in balancing with certain registers of the right hand keyboard. In general, it provides a more subdued effect, by eliminating the soprano and alto sets of reeds. THE BASS/ALTO REGISTERExample 19 pictures this most exotic and seldom-used of the standard reed combinations. The bass, alto and soprano sets of reeds are open and respond for the single note buttons. Only the alto and soprano sets will sound for the chord buttons, as previously shown for the Alto and Tenor (forte) Registers. See example 6.The two octave separation between the bass and alto sets of reeds results from the absence of the tenor and contralto sets and creates the "reedy" quality. The low-high relationship between the single note and chord buttons is the hallmark of the register. The range of the bass set of reeds (C to B) is used to notate the single note buttons in the bass registers. Different upper octave doublings are clearly shown by the standard register symbols. However, the range - one semitone less than a complete octave - is sometimes exceeded in the notation (usually upwards), in order to avoid voice leading which appears awkward. Ambiguity of pitch placement results from the multiplicity of octave doublings and the overlapping of a portion of the tenor and alto reeds by the contralto set of reeds. In fact, some ears may be convinced that a larger range is active. This notation practice, accompanied by the term bassi soli (b.s.) when the upper bass clef area is used, is easily abused. To guide in writing, awareness of the actual pitch range is necessary.  The pitch is readily recognizable in all registers other than the Master

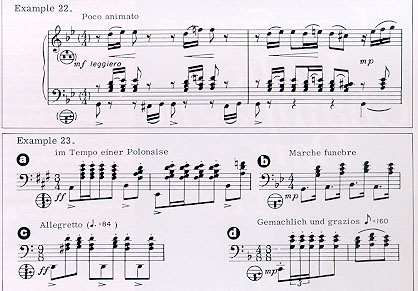

Register. The limited range of 12 semitones is audibly obvious and, written

melodic or harmonic intervals involving tones beyond the actual compass

of a register will sound inverted.

The pitch is readily recognizable in all registers other than the Master

Register. The limited range of 12 semitones is audibly obvious and, written

melodic or harmonic intervals involving tones beyond the actual compass

of a register will sound inverted.Examples 20 and 21 are excerpts which utilize the single note range in bass registers. The first (20) from Henry Brant's Sky Forest for four accordions, involves an imitative duet between two accordions in the same left hand register. In the second example (21), from Alexander Tcherepnin's Partita (1962), the dynamically reduced effect of the bass (piano) Register might perhaps be better suited than the Bass (forte) Register. The absence of the two highest sets of reeds in the Bass (piano) Register will also give the illusion of greater depth since, in fact, the overtones by octave duplication will have been reduced. Upper notes of the chord buttons are delineated more distinctly when sounded without duplications - as in the Bass (piano) Register. By contrast, the confusion caused by the unison and octave doublings obscures these top notes in the Master Register. Example 22, from the second movement of the Concerto for accordion and orchestra by Anthony Galla-Rini, uses chord buttons in the Bass (piano) Register to double a melodic motive and provide a harmonization one octave below the right hand. Numerous dance-derived rhythmic patterns of bass/chord are often used idiomatically in the bass register. The low bass and medium chord provide the characteristic relationship. Example 23 shows several patterns: a) Concerto for accordion and string orchestra (1941) by Hugo Herrmann;  b) Threnody by Arthur Carr; c) Prelude and Dance, Opus 69, by Paul Creston;

d) Divertimento in F, Opus 59, by Hans Brehme.

b) Threnody by Arthur Carr; c) Prelude and Dance, Opus 69, by Paul Creston;

d) Divertimento in F, Opus 59, by Hans Brehme.The proximity of the switches allows the buttons and these levers to be activated simultaneously. Instant octave changes and chord inversions are possible at slow to moderately fast tempi. Example 24 illustrates this technique: a) Overture to Zampa by Ferdinand Herold (Galla-Rini); b) Concerto for Accordion by Eugene Zador; c) The Rosary by Ethelbert Nevin (Galla-Rini); d) Sonata (in one movement) by William Kuehl (arrangement by the composer for two standard accordions); e Un Larme by Modeste Moussorgsky (Balestrieri). |