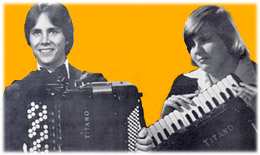

Monica

Slomski, the 1979 U.S. champion representing the accordion teachers' guild,

previously won this title in the American Accordionists' Association's 1975

championship, after which her virtuosity earned her the silver medal, second

place, at the 'Coupe Mondiale' in Helsinki. She took her bachelor's degree

with accordion as her major in her hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut,

and is currently pursuing her doctorate in Kansas city, Missouri. Monica

Slomski, the 1979 U.S. champion representing the accordion teachers' guild,

previously won this title in the American Accordionists' Association's 1975

championship, after which her virtuosity earned her the silver medal, second

place, at the 'Coupe Mondiale' in Helsinki. She took her bachelor's degree

with accordion as her major in her hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut,

and is currently pursuing her doctorate in Kansas city, Missouri.The 1979 U.S. champion representing the American Accordionists' Association, 17 year old Don Severs, from Des Moines, Iowa, has studied accordion since he was six. For the past few years, he has traveled 400 miles to make the round trip from his home to the Kansas city campus of the University of Missouri for lessons in the school's music department. Van Cliburn became an overnight American culture hero after winning the International Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958. His spectacular musical career was launched by a contest victory, confirming that competition has frequently been the springboard for the highest echelon of young instrumentalists. Competition is known to bring out the best in us, to set goals and create standards, to goad us on to break existing records. History verifies that societies, which eliminate competition, invariably slip into mediocrity. The accordion community has long been a staunch advocate of competition. For years, contest concepts have been employed to elevate standards at the international, national, local and intramural levels. The phenomenal growth of accordion competitions may well be a result of the instrument's yet undeveloped exposure possibilities in other areas. Whatever the reasons for the importance contests have assumed among accordionists, substantial benefits have been derived through this activity. There is an obvious correlation to be found in the relatively rapid elevation of accordion playing standards over the past few decades, during which time competition has been a major source of musical input. Educators cite many valuable learning benefits, which the student may gain from accordion competition. Teacher-accordionist Frank Mucedola of Auburn, New York, says there is no better application of the adage "If at first you don't succeed, try, try again." Educator Tony Dannon of Dearborn, Michigan, whose students are frequent contest winners, stresses that youngsters learn to function under pressure and this experience is then invaluable in all areas of life. Composer and concert accordionist Anthony Galla-Rini of California notes that a student is subtly propelled toward advancement in knowledge and technical ability as he progresses to the next higher contest category each year. Tito Guidotti, a Los Angeles teacher, composer and accordionist, points out that students benefit from exposure to different types of literature which is frequently encountered for the first time at competitions. Frank Gaviani of Boston, a renowned composer and teacher, observes that competition helps the student because he is compelled to practice more intelligently for this special event. The contest learning experience is indeed multifaceted. There is little question about its musical significance, but comments by sociologist Dr. Douglas L. White of the Henry Ford Community College, may shed light on aspects of personal growth which the contest offers to young competitors. The sociologist sees a relationship to attitudes with respect to perseverance. Children learn to persist in the face of adversity. It is heartbreaking not to win a prize when one has practiced long and hard. And, it is at this time when the love and support of family is so meaningful. The family has an opportunity to demonstrate just how important each member is by being supportive of the one experiencing disappointment. Such introductions to, and development of persistence is of inestimable value. It teaches children how to lose gracefully "Accordion competition helps to develop modest aplomb in youngsters. When one wins big in local, regional, or national contest, victory may go to one's head. Learning that one can never be too certain of his position, tends to temper excesses. To take the plaudits of the public graciously is an important skill. In other words, Sociologist White concludes, "children must also learn how to be winners". Contests stimulate and sustain interest among the younger musicians. Their far-reaching impact generates enthusiasm among students, teacher and parents, while creating educational and entertainment opportunities galore. "Accept your losses proudly, acknowledge your winnings humbly and above all, continue to strive for the greatness with which you are blessed," says accordionist Ray Lewis, who teaches in West Covina, California, and believes that lessons in living, as well as in music, are to be learned from the contest situation. Accordion contests today sport more than 100 competitive categories, some of which require prior qualifications and others are open to all accordionists. Classifications include solos, duets, combos, ensembles, bands and orchestras, representing all styles of music from classical to pop to ethnic, at age and study levels tailored to meet the needs of thousands of participants who receive cash prizes, trophies, medals, ribbons, certificates and lavish dollops of self-esteem. In the United States alone, music school, state, regional and national contests bring together tens of thousands of contenders in accordion competitions and festivals which provide the place for young people to display their musical accomplishments while contending for prizes and distinctions in their "struggle for superiority or victory," as the dictionary defines "contest." Aldous Huxley, the prominent English author said, "There is the greatest practical benefit in making a few failures early in life." This statement is certainly borne out by the vast numbers of six, seven, and eight year olds who plunge fearlessly into accordion contests. Why do thousands of accordion students spend countless hours in preparation for contests? Why do they travel hundreds and hundreds of miles by car, bus, train, or plane to enter competitions? Why do teachers devote substantial amounts of time and energy preparing soloists and groups for competition? Why do noted educators, composers, and performers offer their services as adjudicators? Why do parents plan holidays, weekends, and vacations to conform to contest schedules so they may accompany their youngsters to these events? Why do scores of local, state, national, and international associations become enthusiastic sponsors of regular competitions? The most apparent answer to all these questions is simply that contests offer spectacular returns. Indeed, contests stimulate and sustain interest. They generate enthusiasm among students, teachers and parents. They create educational, social and entertainment opportunities. There are significant benefits derived from contest-related travel, exposure to new and exciting experiences, and the lasting friendships found through contest camaraderie. Composer and concert accordionist, Dr.William Schimmel, who wrote the 1979 world accordion championship test piece, The Spring Street Ritual, says, "It's true, there has been an increase in virtuosity due to contests, but not necessarily in artistry." Most educators, however, concur that new heights of artistry and virtuosic standards have been attained in the accordion world largely through the stimulus of competition. In fact, young students today are proficient at playing many of the works, which only the most accomplished artists were competent to perform years ago. Donald Balestrieri, a noted composer, editor, concert accordionist and faculty member of San Diego State University in California, is emphatic in stating, "Contests inspire students to strive for, and attain, better musicianship by focusing greater attention on musical details such as accuracy, phrasing, technique and other interpretive aspects. The younger student's interest and awareness is often intensified through exposure to advanced players at competitions." Some teachers conclude that regular lessons can only point out weaknesses; contest preparation and adjudication indicate a more forceful demand for correction. Moreover, a deadline is set; the piece must be ready for perfect concert performance at a specific time. Esteemed teacher and jazz accordionist Tony Dannon believes that students might "not remain long enough on one selection to learn it properly," were it not for the more stringent requirements of contest performance. "The accordion is portable - marvelous as both a solo and a group instrument - ideal features which enable students to play with other musicians. The musical benefit and social stimulus of playing music with others is a unique advantage," says Harley Jones, who has frequently adjudicated at the Coupe Mondiale, the international accordion championship, and is a well known performer and teacher in his native New Zealand. In recent years, members of the music community have been thinking deep thoughts about competitions in general and their very validity. Rosalie Leventritt, one of the principals behind the prestigious Leventritt International Competition (established in 1939 in memory of Edgar M. Leventritt, a New York lawyer and music lover), recently stated that "Competitions are breeding a kind of artist we are not eager to foster."  Ms

Leventritt believes that competition winners all over the world are developing

into skilled technicians who play everything by the book without imagination

or commitment. They play for the jury, and they are not going to take any

chances. Jury members, most of whom are teachers and, regrettably, sometimes

pedantic in their musical outlook, get disturbed when a flaming temperament

comes up, interprets in a highly personal way, drops notes, aims for a big

line rather than precision. This is not musical playing, and adjudicators

may frown upon such liberties being taken, according to Ms Leventritt. Ms

Leventritt believes that competition winners all over the world are developing

into skilled technicians who play everything by the book without imagination

or commitment. They play for the jury, and they are not going to take any

chances. Jury members, most of whom are teachers and, regrettably, sometimes

pedantic in their musical outlook, get disturbed when a flaming temperament

comes up, interprets in a highly personal way, drops notes, aims for a big

line rather than precision. This is not musical playing, and adjudicators

may frown upon such liberties being taken, according to Ms Leventritt.All too often, contest hierarchies have been less than happy with some of the winners selected by adjudicators. The feeling was that they were talented but not yet ready for a major career. Sometimes, non-winners have been viewed as potentially superior. More and more contest sponsors are beginning to think that the maturation of a young musician may be of greater significance that the strongly technical skills which appear to impress many adjudicators. No matter how loudly serious musicians may decry the concept of competitions, it is a fact of life that glamour, suspense and excitement are an integral part of the concert-going experience. One of the problems about musical life today is that we have too many serious musicians and not enough exciting ones. Elmar Oliveira, who recently won a gold medal for his violin virtuosity at the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow, has found that both his schedule of concert engagements and his performance fees have tripled. Yet with all this, Oliveira faced a problem common to many skilled musicians - making a living. To help support himself he played in the pit orchestras of three Broadway shows, Irene, Applause and The Rothchilds. "I've done a lot of freelancing," he comments. It's part of earning a living. It's not always easy - you have to keep the discipline of caring about how you're playing. Whether it's the Beethoven Concerto or Alice Blue gown, every note is important. If you have that attitude, the quality of your playing will keep up. When I was in Moscow, I discovered that some of the other American competitors had never played a commercial job in their lives.  "That

seems unrealistic to me. Many great musicians have played in cafes and jazz

bands. You learn from those experiences - you can't just sit in a practice

room and develop into an artist. You grow from exposure to as much diversity

as possible. I'm constantly being surprised at musicians I meet - and good

musicians, too - who don't know who Thelonius Monk and John Coltrane are.

They have no idea of what they can draw from their own instrument. I admire

a man like Andre Previn, who's a tremendous jazz pianist, who can write

scores, who's an all-around musician. That's what it's all about." "That

seems unrealistic to me. Many great musicians have played in cafes and jazz

bands. You learn from those experiences - you can't just sit in a practice

room and develop into an artist. You grow from exposure to as much diversity

as possible. I'm constantly being surprised at musicians I meet - and good

musicians, too - who don't know who Thelonius Monk and John Coltrane are.

They have no idea of what they can draw from their own instrument. I admire

a man like Andre Previn, who's a tremendous jazz pianist, who can write

scores, who's an all-around musician. That's what it's all about."While Oliveira obviously appreciates what contest victories have done for his career, he stresses his own desire for a feeling of individuality. "Today there are more people playing more notes than ever before. I sometimes think that the element of a player's own style has faded. I try to draw on traditional playing and also on the phenomenal modern schooling that has developed." This 28-year-old musician believes that one's personality should be evident in one's playing. He wants people to say, "This is this guy playing - not just another good musician." Some believe that the maturation of a young musician may have greater importance than the publicity and fuss over winning a major competition. Competition formats are in flux as other possibilities are being scrutinized. There are those who advocate a national jury selecting several highly talented musicians, giving them cash awards and performance opportunities, and hand-tailoring all events to the performer's needs. Others favor concentrating on young artists and subsidizing their careers for at least a period of time. In some countries there is considerable subsidy, under government auspices, available to budding artists. Musicians receive special guidance and a great deal of performance exposure with everything geared toward developing them as top-flight artists. The Western nations, however, have hardly matched Russia and other Eastern countries in providing a notable support system which can foster major careers through concert appearances, recording exposures and performance opportunities. Very recently, the American Accordionists' Association launched a modest but noteworthy program to bring its U.S. championship winners to public attention through concert exposures at world-famous Carnegie Hall in New York City. Dubbed 'Young Artists' Concert Series," the first program spotlighted the 1979 U.S. Accordion Cup champion, Don Severs, prior to his trip to Cannes, France, where he represented the United States at the Coupe Mondiale. Concert Series Chairman Frank Busso said that the AAA plans to further maximize its winner's performance opportunities by initiating numerous concerts across the country in collaboration with affiliated accordion organizations. It is hoped that other fraternities in the world of accordion competitions may follow this precedent. Prominent music critic Harold C Schonberg recently evaluated the many aspects of competitions in an elaborate New York Times article, in which he examined the pros and cons before reaching his decidedly pro-contest conclusions. "Of course all competitions have built-in inequities. Of course justice is not always done. Of course there may be a severe psychological jolt to non-winners. Yet there still is a case to be made for competitions. They have many positive factors going for them. "Entering a competition is, after all, a matter of free will. Nobody in the West has to enter a competition. Nobody is dragged in to it kicking and squealing. And competitions do help launch careers. Publicity has never hurt an artist. It may be that competitions do not themselves make careers. Only artists make careers." Schonberg concludes that first prize in a prestigious competition focuses a good deal of attention on a hitherto unknown (to the public) musician, and there is nothing like the bright light of publicity to make his face and his art familiar to all. |